1976-1992. A very serious, semi-serious biography

To break through, they will have to overcome significant obstacles, because of the competitive nature of this field: nobody dreams of becoming a butcher or a pastry chef nowadays, but many want to become photographers. Just remember that, before them, we have all had our fair share of experiences, failures, sufferings, and blunders.

I just happen to be a photographer

Roberto Bigano interviewed by Alessandro Menegazzo

My mom owned a camera that I would often borrow. The brand was ‘Pearl,’ but it was not a pearl of a camera. I soon yearned to own a serious camera, and so I spent all my savings on buying a Canon AE1. It was sturdy and reliable, with a prime lens: it was a knock-out. It was like graduating from a bike to a car: a gulf between them. I quickly shot my way through the first roll of film, then I ran to the nearest print shop and bugged the owner until he gave me back my printed photos. It was right then that I decided to become a photographer.

Easy to say, but that decision was a bit short of a miracle for me. I reached age 23 with a few confused ideas about life after realizing that a degree in mats was not for me, after a bit of politics, and after much bullshitting. However, I had finally realized what I wanted to be, and that was all that mattered. After a month, the darkroom no longer held any secrets from me, and, with an Agfa kit, I learned how to develop my positives that I would later print in Cibachrome. I now lived for photography, and I wanted to be reciprocated: I expected photography to put bread on my table.

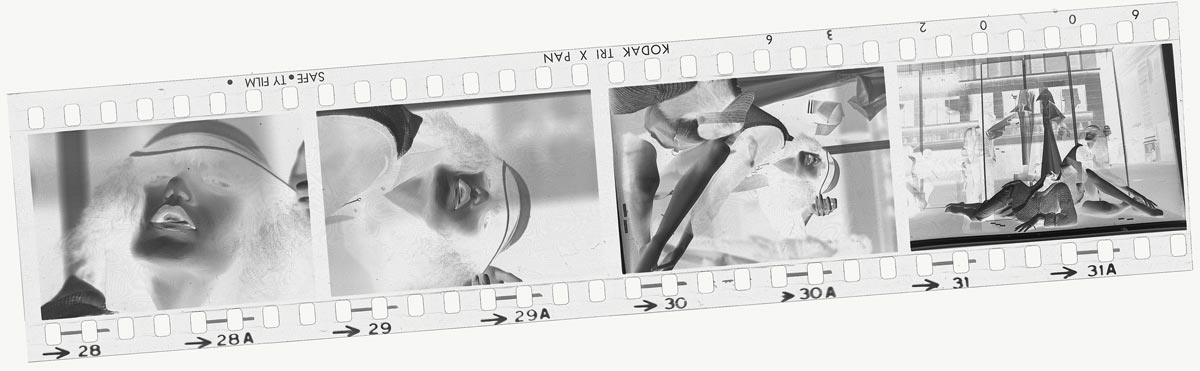

June 1977. Roll N. 0014. My very first strip about dummies. I still didn’t know that many years later, mannequin would become one of my successful subjects. I loved Ilford films, but they told me that pros used the Kodak Tri X, and here it is.

The featured image above: a negative mistakenly developed as a positive, original taken for a glamour shooting.

Early Flights

During 1977, I would make ends meet as an occasional photographer thanks to jobs I would get, mostly, through word of mouth. One morning, the usual friend’s sister’s friend let me know, via a few phone calls, that the local winery needed a picture of a wine bottle. Their catalogue, which was to be printed the next day, needed to be updated and their usual photographer was unavailable. They needed someone to come in and save the day. I was taught to always take advantage of the opportunities that come my way so I told a few white lies and pretended to have shot as many wine bottles as Giorgio Morandi had painted in his still life paintings (since they would not have had enough time to check). The picture was then my problem.

I did not lose spirit and I thought: bottle=reflection, reflection=polarization. I bought two polarizing filters and a Kodak EPY 5×7″ tungsten film. The resulting picture showed something that resembled more a green cardboard cut-out with a sticker on it, than a real bottle: it was flat with no highlights. Unfortunately, I didn’t have time for further experimentation so I went to meet with my client pretending to radiate fearlessness.

The small, peaceful man smiled at me, without hiding the stress due to the urgency of the job. “Well… I’d say we’ve got it”, he commented. “Of course, the photographer’s hand is different, and you can tell, but we knew this from the start…. Plus, there’s no doubt that this is a bottle… How much do you want for this shot?” I was very much aware (and felt guilty about it) of both the image’s flatness and the client’s urgency, so I decided to ask for 10,000 lire (about ten dollars) which was pretty low even for 1977. “It’s more than reasonable”, said the man. So I went on for a good 10 minutes telling him, in many different ways and repeating myself to the point of obnoxious, that it was a promotional price (I was afraid I’d blown my cover of seasoned professional), that my normal rates were much higher, that I’d given them special treatment hoping to work together in the future but they shouldn’t think they’d always be so fortunate, and so on.

For my client Ovomattino, I needed to photograph cluck hatching on some hay, on a white background, in my studio. It was not easy, like every project tackled without knowing how to. After being pecked many times and failing to get the cluck out of its hiding place, we had to ask for the help of the owner. The lady, knowing her chicks, soon recovered our fugitive and tied its legs together to keep it still. It resulted in a very eloquent expression on our subject, as you can see. Lens: Schneider Symmar 240; Light: Flash Broncolor; Film: Kodak EPP 4×5.

Canon, Blow Up and Nikon

That same year, I gave in and bought a Nikon, seduced by the cult-movie ‘Blow up’. After selling my trusty AE1 and after a few tears, I bought a Nikkormat and two lenses (a 24″ and a 105″).

In ’78, after it being postponed many times, I was drafted into the army and (incredible, I know) they made me photographer. I was stationed at the Military Academy in Modena and, between the cadets’ swearing-in ceremonies and the many receptions, more yards of film than bullets were needed. So my grand day came: the cadets were to guard the ‘Altar of the Fatherland’ and would later be received at the Quirinal by President Pertini. “Bigano, we trust you, don’t make us look bad, otherwise you can forget your leave and you’ll spend the rest of your time taking ID pictures,” shouted my commanding officer. His treatment jinxed me. I was penalized from the start by my weapon: they didn’t allow me to use my Nikkormat, which I knew like the back of my hand, but I had to use an old Rolleiflex instead.

I was grandly received when arriving at the President’s office, and was solemnly announced (“The photographer first!”) by a guard who invited me to position myself wherever I found most appropriate for my delicate role. Such a glamorous introduction could only be followed by a terrible flop. Forgetting that the Rollei only has 12 shots, I missed the crucial handshake between President Pertini and the Captain, since I was busy loading a new film in the camera. The terrible mistake left me so shaken up that I left the exposed roll of film on the President’s desk! My only choice now was to break through the armed guards, barge into the President’s office and ask for my film back before the bomb squad disposed of it. At last, however, my luck turned when the official Presidential photographer realized what had happened to me. After hearing my story, he took pity on me, took the film out of his magic Nikon and handed it over, saving me. Wherever he is now, I would like to thank him with all my heart once again. Since then I have never stopped believing in solidarity amongst colleagues.

I have always found shop windows and mannequins to be some of my favorite subjects. The picture below, taken in Beverly Hills, CA, was supposed to be published in my book on the United States “A Big Country” by Prentice-Hall of the Simon & Schuster group. For different reasons, however, the book was never published.

Camera: Linhof Technika; Lens: Rodenstock Sironar 150; Film: Kodak EPY 4×5. While in the US, I developed my film at the A&I lab in Los Angeles, CA; I believe it to be the best in the world. Using the Ektachrome 64 and 50T, in a 4×5 format, I obtained results that, to this day, match up to a professional digital camera.

“Venezia ’79 la fotografia”, Lee Friedlander and my first assignments.

In 1979, Venice hosted an event that has never since been repeated: 42 photography workshops taught by the most famous photographers in the world, organized by the renowned ICP, International Center of Photography of NY. Photographers such as Lee Friedlander, Harold Edgerton (who invented the electronic flash and created the image of the famous milk drop exploding in millions of micro-drops), Chris Broadbent, Aldo Ballo, Arnold Newman, and many more, were there.

Lee Friedlander was my idol at the time: I pretty much worshipped his photography. The opportunity to participate in his workshop (thankfully, my English was good enough) should have made me the happiest man on earth, and I should have just kept my eyes and ears open, and my mouth closed. However (I have already said that I was still a bit confused at the time), seeing my idol on my same level, made of flesh, walking on my same ground, created in me the need to debunk his divinity. I challenged every single one of the points this Master presented, looking not for a needle in a haystack but in an entire barn. Exhausted but a true gentleman, the great Lee told me that I could become a great photographer if only I spent as much time on my pictures as I criticized other people’s work. That was the greatest lesson I learned there.

Not at all disheartened by all the mistakes of my youth, I was aware that it was time for me to roll up my sleeves and do things seriously. If my mother gave me my first camera, my sisters provided me with my first real client, while working for a clothing store. The owner had a zinc ornament with the company logo that he would proudly display on his desk as a paper-weight. He knew I was something of a photographer and asked my sister if I could take a picture of the medal thing. So I took the object outside, sprinkled some silver glitter on it, and took a picture on a vertical axis with a cross-screen filter. When I showed him the picture, his eyes sparkled. I was bold enough to then ask for 120,000 lire (about 120 dollars) in 1979, and he paid up, no problem. It was not bad for my first job, especially since it led me to my second one. “Since you’re so good,” he said, “I’ll have you shoot my new fur coats.” The models did not come straight from the catwalk, but they still looked good and helped my lens get used to the ‘scent of a woman.’ Joke aside, the photoshoot was not the greatest, to be honest, but the client liked the results and paid me a whopping 350,000 lire (about 350 dollars) on the spot.

A picture from the Scandinavia trip. Stockholm, Sweden, window with a vintage dummy and black gloves.

September 1979. Camera: Nikon FM, Lens: 50 1.4, Film: Ilford HP5.

With the money, a travel buddy and I left for a trip to Scandinavia. I had read somewhere that spaghetti, sauce, and parmesan cheese would open many doors for us in those northern countries, where we would have been welcomed with open arms. We wanted to see if it was true. Spent 13 days in the north of Europe, and we were guest of young attractive northern girls for five of these nights. Obviously, we documented this adventure on film.

This way, alternating travels (like oxygen to me) to daily work, juggling between clients, events, and increasingly essential people, my life has continued for the past 20 years like an endless film. And so it goes on, hanging from a tripod, peaking from behind a frosted glass or playing like young and fast Leica M3.

Bolla Vini (I believe, James Bond in “From Russia with Love” orders a glass of Soave Bolla wine) was my first important client, thanks to of one of those lucky chances in life. I worked for Bolla for many years, doing many different things. The above picture was the key image of Bolla campaigns for years.

Camera: Plaubel; Lens: Schneider Symmar 240; Light: Flash Elinchrom; Film: Kodak EPR 4×5.

Seize the Time

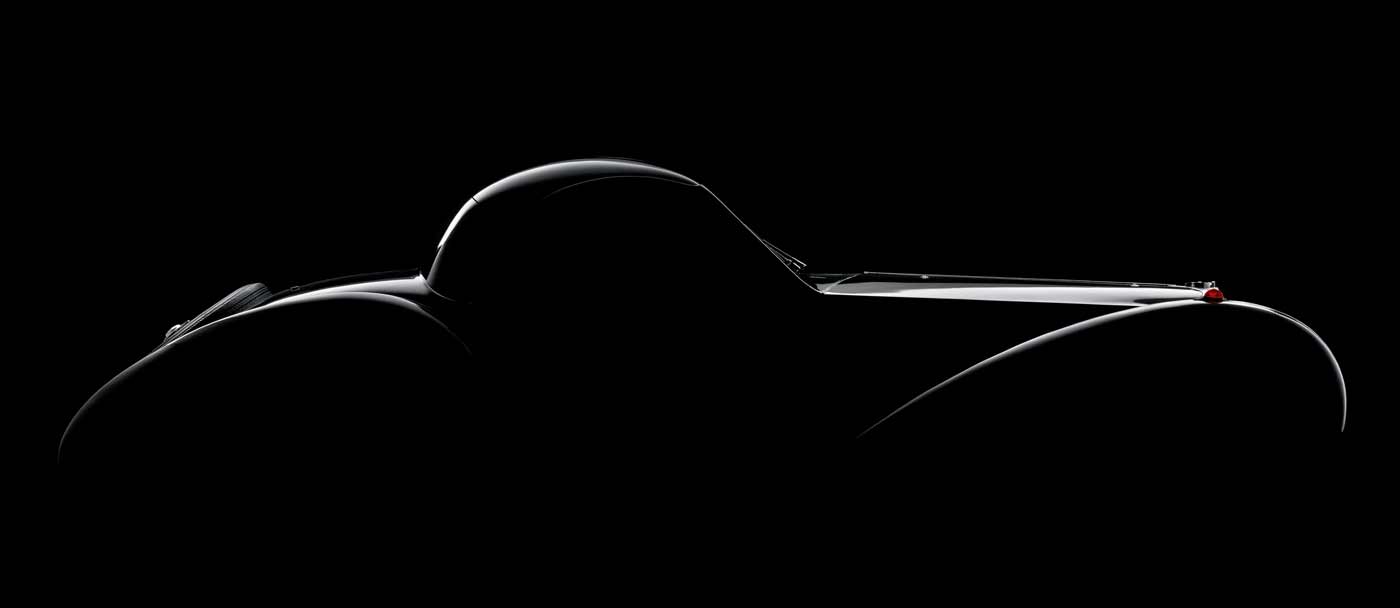

In the 20s, it would flash by at 200 km/hr while the other pilots could only glance at its beauty for mere moments. Now, She and I were looking at each other in an enchanting silence while I was gently touching her with the light: the divine Bugatti, mother of all race cars, mother of all exclusive cars.”

The acceleration that seemed to stop my heart, the deafening rumble of the engine that I felt deep down in my bones, the extremely long hood that reminded me of a Spitfire fighter plane, the intoxicating scent of gasoline, were all such vivid emotions that it could not just be all a dream. Stepping out of the Type 35, I thought that if a passenger could feel those emotions, what about the driver? I then understood that Bugattis were not just legendary vintage cars but live creatures fathered by the genius of Ettore Bugatti, a race horse lover born in Milan – Italy and emigrated in France – meant to be “Les Pursangs des Automobiles” (the thoroughbred of cars). I realized the task that I had been given was not just a show of respect but a sort of initiation.

I had the extraordinary opportunity to travel in this legendary car: the Bugatti Type 35 Grand Prix, 2000 cubic capacity, 8 cylinders, 24 valves, compressor, 150 horsepower, over 200 km/hr. It was running through the glamorous 20s. This picture was taken at the Bugatti manufacturing plant in Campogalliano, Italy.

But let’s start from the beginning. I cannot tell you how this all started, how things changed, how the wind turned. Before I was just one of many, a good photographer with his talents; there are hundreds, thousands, tens of thousands. I was always wondering how one becomes something more than a good photographer, what wall one would have to take down to reach the next step. One day, all of a sudden, I realized I had jumped to the next level, I was taking pictures like I had never done before and I was assigned jobs that I used to consider above my reached, not too long before. I was being contended between clients so important and knowledgeable in matters of photography that I thought would choose the best photographers, and definitely not me. One day, while I was flying to Paris for a photo shoot, I thought back to the days when I was taking “looser pictures” for “looser clients” like a “looser photographer”. My memories were so clear and precise that seemed to be from the day before.

Why was I now lounging comfortably in a first class seat sipping a glass of good brandy while cruising trough the clouds? Why was I not brought down to earth by all the curses yelled after that cluck that did not want to be still, that did not want to help me or my client? From larva I had blossomed into an enchanting butterfly, but what had happened to the secret of the cocoon? What had I done to go, all of a sudden, from being a good photographer to an important one, to becoming the ”Voila monsieur le Photogrape Superstar” like and executive of Franco Maria Ricci France had welcomed me? I had missed that transition, but it had to have happened. It was a much longer and more gradual transition that I might have realized and one day I had finally seen it. I was now looking at myself in the light of the new and important events in front of me. I had seen myself grown up, likes those relatives that only came to visit every few years and would always say “you have grown so much!”

The Year of Grace 1992 and Beppe Maghenzani

Regarding these critical events that poured over us like a purifying rain over the plague, I have to say that were concentrated in the year of grace 1992, and that marked the most crucial change in my professional life; every single one should be described in detail with all its developments and implications (in photography and life). However, in the limits imposed by this biography, I chose to mention the Bugatti event.

Everything started with a phone call from a copywriter friend that I had met while in the army, Beppe Maghenzani. Beppe was part of an overly ambitious project: to revitalize the Bugatti brand. Part of the project comprehended creating a book that would illustrate the story of the Bugatti legend.

The initial thought was to have a photoshoot themed “The Bugatti spirit today in Alsace,” a study of the legend’s birthplace. It is supposed to be not only a historical commemoration but also, as the title said, but a spiritual evocation. For this intricate work, halfway between the archeological excavation and the mediumistic session, my friend Beppe thought of me as the best person for the job. Of the “ruins” of the myth, there was not much left, according to initial surveys. On the eve of the project, I received a call saying that the project was off because there was hardly any material (and the “sprit” would drop even lower) and not worth it.

I do love this picture. My great friend and mentor, Beppe Maghenzani the day of the presentation of the Bugatti EB110 in Place de L’Etoile in Parigi.

Beppe grew so attached to this cause that decided to put everything in my hands. “Send Bigano by himself: if the results will not satisfy you, I will pay him out of my own pocket,” he said to Romano Artioli, the man who had relaunched Bugatti. Faced with such passionate conviction, he could not say no. With all the responsibility on my shoulders, I left armed with less luck than Cesar (who went, saw and won) and saw very little. After a couple of days, I received a call from my friend looking for reassurance on his convictions. “Beppe,” I said, “I working on it, but here the situation is pretty critical.” “But don’t worry, we’ll find something,” I reassured him.

I followed every lead like a bloodhound. I rummaged through the memory of the locals, searching for the stories of fathers and grandfathers, looked through books at the local library and through newspapers archives. I run around like a lost soul for what was left of the headquarters and plants. I visited the museum of the automobile in Mulhouse, France roaming through the rooms like an art scholar would walk around the Louvre, the Prado or the National Gallery.

Molsheim. Chateau St. Jean, former Bugatti headquarters, abandoned by still fascinating.

The first encounter with the Divine was a blinding vision. The Bugatti Royale was right there, surrounded by the most famous vintage cars in the world, also Her rivals: the Hispano-Suiza, the Rolls-Royce, the Packard, and many more, that all looked like humble servants next to the Bugatti. Compared to Her, the others supported antiquated aesthetics and engineering: they looked like luxury stagecoaches with a hood to cover the engine.

The Bugatti Royale was a purebred, gorgeous and gracious in its seven meters of length. It was enormous, had the most oversized wheels, was the longest, the tallest, but still the most elegant. Her functional and aerodynamics lines experimented a unity and a harmony of style that anticipated the “industrial design” of the 50s. That design and form would smoothly conceal the captivating exuberance of an eight-cylinder motor for an impressive 12,773 cubic meters capacity that seems to define once and for all the original idea of a car.

I took this picture for the book “Divina Bugatti” published by Franco Maria Ricci.

Bugatti Type 41 Royale Coupé Napoleon (1929). The personal car of Ettore Bugatti – Engine:12,763 cc / 779 cubic inches. Courtesy: Museé National de l’Automobile, Mulhouse

Ettore and Jean Bugatti

Ettore Bugatti himself designed his creations (together with his extremely talented son Jean, who later took to the drawing board alone). This extraordinary man had attended the Brera School of Art as a youth, yielding to an artistic streak inherited from his father Carlo (a fine cabinet-maker). This flair had also gone to his brother Rembrandt, the talented sculptor whose works include the little elephant triumphing on the Royale’s bonnet. The founding genius to the Bugatti firm also demonstrated an astonishing ability for mechanical engineering and an amazingly eclectic mind in general.

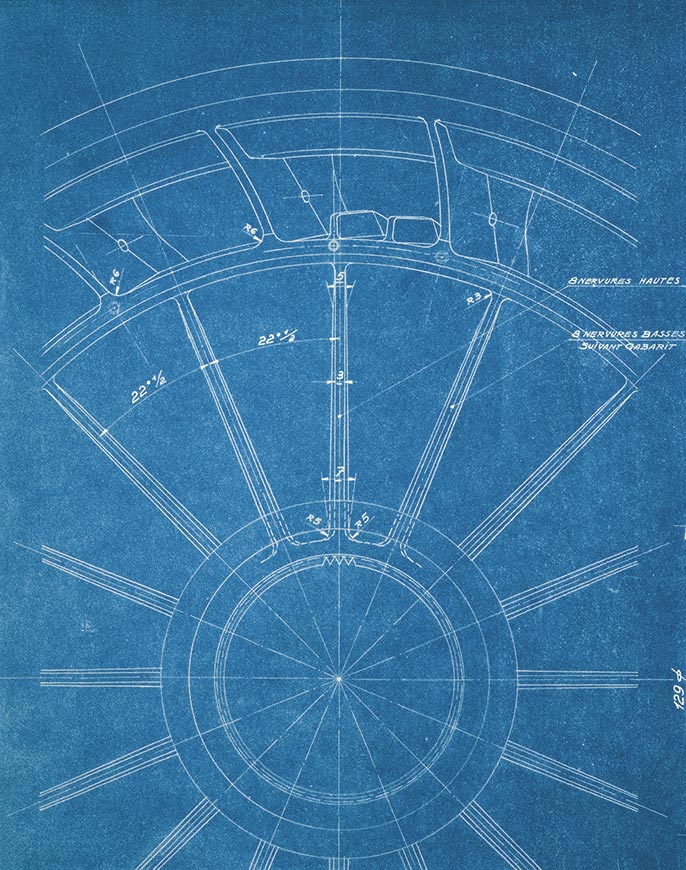

An example? Just take the engine block, the alloy wheels, the three valves per cylinder, the compressor, the double camshaft and four-wheel drive: they were all first previewed by this forward thinker of a man who had built his first car at the age of 20 and who personally designed everything down to the ‘ergonomic’ interiors to his company’s automobiles.

Roue Bugatti brevetée en aluminium coulé – 27 july 1932 (Patented Bugatti wheel in cast aluminium – 27 July 1932). Period heliographic copy of one of the most famous technical drawings by Bugatti, and more precisely the detail of an alloy wheel used for the Royale. Ettore Bugatti was extremely demanding and expected almost obsessive attention to detail from his engineers and designers. Many Bugatti ‘factory drawings’ are authentic masterpieces

Just to get an idea of what sort of person this genius was, here’s an anecdote that gave me goose bumps. One day the head accountant came to Ettore Bugatti with a concerned air and asked to talk to him: the sharp downturn in the market meant they had to make 200 employees redundant. After a sleepless night, Ettore gathered together all the personnel in the biggest warehouse. The mood was a tense one and there was total silence when the ‘Boss’ began his speech: “if fewer cars are being sold, then we’ll build trains,” he announced to all the men, who gaped at him in astonishment.

The train that left the Bugatti plant heading for the French railways was practically the TGV released 50 years early: its lines were reminiscent of the super-aerodynamic ones seen on the Tank, daughter of the wind of victory at Le Mans; and the drivers’ cabin was set up higher than the passenger carriages, as with the Boeing 747 flight deck. While steam trains were slowly chugging and grinding along tracks all over the world, the Bugatti train – powered by four super-versatile and mighty Royale engines – was breaking all the records, speeding along 140 passengers and the same number of sumptuous seats at 130mph in 1936.

Okay, I think I’ve managed to paint enough of a picture now for you to appreciate my awe and quivering when faced with the legend, when I understood the full reach of my involvement, and that I had the overwhelming responsibility of portraying The Divine for the aesthete Franco Maria Ricci. Perhaps you can understand why, when looking at the Polaroids on a bleak Alsace night, a long time after my first visit to the Automobile Museum, I despaired of succeeding. I was afraid that The Divine, feeling violated in its own temple, the same way an Egyptian queen might in the pyramids, would unleash its curse against me.

Renata Kettmair and Romano Artioli

You’ll be wondering at this point what the editor Franco Maria Ricci has got to do with Romano Artioli and the Bugatti project in Alsace. You’re quite right: we’re back to where we left off, at my first visit to the Automobile Museum in Mulhouse. Well, when I headed out of that temple to The Divine with a handful of respectable daytime shots, I had the feeling that I’d return. Nevertheless, I was just as sure that I’d photograph The Creations the way I wanted, using my studio lighting. And I was just as aware that nothing and nobody would allow me to stuff real cars worth millions into my handy little back-pack. Only God would know how to solve this teaser. But our fate is evidently already written in the stars.

And so I returned to my base with the fruits of my mission in Alsace. The appointment with the client was in Ora, near Bolzano. I was met by Romano Artioli’s wife, Renata Kettmeir, who wanted to see the shoot straight away, leaving me feeling a little thwarted: I’d have preferred to personally handle the presentation of what I’d photographed, particularly given the complexity of the project. “Nice work,” commented Mrs. Artioli after the first few images. “And since you’re doing such a good job, please feel free to go to Campogalliano to finish it.”

Romano Artioli, in his office in Campogalliano. Lower left: Rembrandt Bugatti’s roaring elephant

At the new Bugatti premises I was immediately received by Romano Artioli, the man responsible for a great turning-point in my life. If I was surprised at not having been made to linger even a second in a waiting room to meet such a busy man, I was literally speechless when Mr. Artioli began discussing work, without even asking me to see so much as a single photo. “Fine, Mr. Bigano,” were the words he opened with. “You are to document the history of new Bugatti, its cars and the company. You are to illustrate the birth of the legend through every stage in the journey. I want it all: the successes but also the failures, the moments of euphoria and the periods of suffering, the race triumphs alongside the mistakes, the designing, the mechanics’ sweat, the wind tunnel – in short, everything right up to presentation of the new EB110 to be released next year in Paris, and the following Gran Gala evening at the palace of Versailles.”

“But Mr. Artioli,” I replied, embarrassed and shocked. “Do you realise you’re asking me to take on a colossal job with serious difficulties and responsibilities? How can you be sure I’m capable of coping with it if you don’t know me and you’ve never seen a photo of mine?” “Listen,” Romano Artioli answered. “I’ve never yet found a photographer to please my wife. If you’ve made a good impression on her then you must be excellent.” I swear, that’s exactly what he said.

The great adventure of “Bugatti Automobili”

That’s what he said and that’s how the great adventure started – an enterprise that would see me work for Bugatti almost full-time for a whole year. It was a thrilling experience, an incredible situation. The company was a true gem and I was treated like a prince; I felt like Benvenuto Cellini at the Medici court. Wherever I went and whatever I needed, I was assisted in everything and for everything by a legion of secretaries of all races, each one prettier than the next.

Cleaning Works at Bugatti Factory, Campogalliano.

For his part, Mr. Artioli not only wanted me on board his twin-turbine Mitsubishi, but as the great salesman he was, he extolled my talents to every visitor to the company (and they were all ‘heavy calibre’): “Allow me to introduce the best photographer in the world,” he would say. “His photos have a soul. Even Franco Maria Ricci raves about them.”

Franco Maria Ricci again. Just a quick introduction to the character. In the early ’50s he was a young man who could afford the dream of a Ferrari. He also had a sort of veneration for books. In ’55 Ascari died in Monza driving a Ferrari. Deeply disturbed, Ricci sold his Ferrari and bought a printing-house. This marked the beginning of his supreme era as sophisticated editor. In the ’80s he launched FMR, a magazine focusing on the art of beauty. The FMR initials were well-calculated: they also stood for Franco Maria Ricci, and when read in French they were pronounced like the word EPHEMER (ephemeral). FMR was the review of the ephemeral, or rather of the sublime things in life. The United States release of the debut issue was something of a spectacular event: eight cargo Jumbos landed at the JFK airport carrying a million copies of the magazine. FMR would become the world’s most-read review of beauty.

Franco Maria Ricci, who already wanted to celebrate the Bugatti legend, suggested to Romano Artioli, the car company owner, the idea of a book on the famous make. They reached an agreement and the idea went through. Naturally, Artioli mentioned to Ricci “the best photographer in the world”, strongly encouraging my candidacy for the job. Ricci, as expected, was sceptical. He wrinkled his nose, dissolving his calm aesthetics, like a lake’s surface rippled by the wind. “I have my photographers, ones I trust”, he coughed out, straining at a half smile. Nonetheless, Artioli’s insistence earned me a meeting with Ricci: “Go and take a few shots. We’ll see,” he said, to get rid of me.

Controlling the aerodynamic of Bugatti EB110 Prototype at Wind Tunnel at Pininfarina Factory

Franco Maria Ricci and “Divina Bugatti”

I felt well-equipped on my departure. 145 different accessories packed in the trunk of my station wagon. For months, I had been working on how to build a mobile set around a Bugatti, on location. Before violating that holy ground, I carried out a test: I photographed a Lancia Thema in a large shed. It worked, so I decided to go ahead.

Upon arriving at the National Automobile Museum of Mulhouse in Alsace, I embarked on my nocturnal marathon. Cloaked in the atmosphere of suspense, in the eery silence, I came face to face with The Divine. The situation reminded me of one of Hemingway’s stories: the bull and the lion, still before the charge. I was almost worried that the steel muscles would explode, at any time, in all their power and the beast within would run me over like a train. I had an emotional outburst, I felt as if I were running a fever. Like a robot, I kept shooting and opening Polaroids. I was looking at her but I could not see inside her. Fatigue and tension made everything even more dramatic. “What am I doing here in France, in the middle of the night, in a dark museum? Why didn’t I stay home?”, I started thinking.

All of a sudden I had reached the turning point: I opened yet another Polaroid, but this time I found the courage to look at it with a photographer’s eye. I had recognized her, The Divine, in all her dazzling beauty. “I am yours. Only you will be able to possess me,” she was saying. I started dancing as if I was in the middle of the Rio de Janeiro carnival parade. I didn’t feel tired anymore. “I’ve done it!” I said, my voice echoing in the empty museum.

I’d finally gotten a hold of the situation. I’d jumped on the wild horse and was riding as a Native American would.

The set of “Divina Bugatti” at Museė National de l’Automobile, at Mulhouse, France.

Above, The “turning point” Polaroid. Before this one, I was totally discouraged. After seeing this I realized that I got it.

I arrived at Franco Maria Ricci’s, feeling confident and appearing as cold-blooded as a contract killer. I knew I was in the presence of one of the most refined editors the world had ever seen, but I also knew that I could not fail: if he had any taste at all – and it could not be otherwise – he could not still be indifferent after seeing my work.

Ricci received me with a smile that was more gentle than polite. The smile you would give a child who is showing you their drawing. After his eyes settled on the first photo his expression changed and suddenly brightened. “But they are… lit!” he whispered to himself. “Of course they are! Did you think I would bring you the dark ones?” I answered in a friendly yet amused manner. It felt like I was watching from the outside, as if I were the spectator to a film. Franco Maria Ricci picked up the phone. “Come and look at something sensational!” he said and then ran down the corridor enthusiastically. “Call the others and tell them to come to my office!” He looked at me excitedly in front of all his associates, as if I were a superhero, and offered me some incredible projects: on Spanish baroque style, on medieval armor, on the town of Parma, and on French cabinet-makers. He had basically just assigned me all his future projects.

I had managed to impress Franco Maria Ricci, the king of aesthetics! To think that only a few years before, it was just me and my camera lens!

I took this picture in the first session. It was the only one rejected by the publisher as “nonobjective.” The original remained in a drawer for 17 years before becoming my best seller and icon. I can say this photograph allowed me to send my daughter to college in the United States.

Bugatti Type 57SC Coupé Atalante, a 1938 dream car designed by Jean Bugatti. Photo by Roberto Bigano

Courtesy: Musée National de l’Automobile, Mulhouse, France.